Bolstering the Richmond Region’s Resilience Toward Extreme Heat

Like everywhere else on the planet, the Richmond Region is susceptible to a variety of risks, and among the most concerning are those related to climate change. Droughts and floods, warming oceans, rising sea levels – all of these conditions and more pose both near- and long-term risk to human health and economic prosperity. To help mitigate these potential dangers and better prepare the region to meet current and future challenges, PlanRVA promotes activities to improve the region’s resilience*. In the first of a series on the topic of resilience, today’s blog covers PlanRVA’s activity in understanding and addressing extreme heat.

More than floods, more than drought, even more than natural disasters like hurricanes, extreme heat* presents the most danger to the Richmond Region. While the damage wrought by flooding bears the costliest economic burden, the human toll from extreme heat is the deadliest. More people die on average annually from extreme heat in Virginia than any other natural disaster.

*Defined Terms

Resilience planning ensures that communities can adapt and thrive amidst challenges.

Extreme heat is when the daily temperature reaches over 90 degrees Fahrenheit. Humidity and consecutive days of extreme heat can exacerbate stress on the body, especially when the temperature at night does not drop below 80 degrees as the body cannot rest and recover.

Hot Spots are areas of elevated temperature due to re-radiated thermal energy from the built environment and human activities.

An urban heat Island occurs when a city experiences much warmer temperatures than nearby rural areas.

Heat vulnerabilities include, but are not limited to homelessness, lack of AC, difficulty paying utilities ("energy burden"), age (3 and under or the elderly), pregnancy, chronic illnesses (especially cardiovascular or respiratory) and working outdoors.

Helping mitigate against extreme heat can be done in several ways, most of which involves all things green. Increasing the tree canopy by planting more trees, dedicating more land to green space, converting roofs to rooftop gardens, even painting roofs white, all of these measures serve to reduce the temperature of particular environments, both in urban and rural areas.

While PlanRVA is encouraging the region’s nine jurisdictions to make a “gray to green” transition, the organization is developing a regional analysis that will enable local leaders to better understand the extent of the problem and prioritize the areas where the biggest impact can be made.

PlanRVA is the recipient of a $10,920 matching grant from Department of Forestry under the Urban Community and Forestry Grant Program. The funds support the Richmond Region Urban Cooling Capacity Analysis Project, a three-phased initiative that will give planners empirical data on the region’s hot spots*.

Mapping Heat Islands

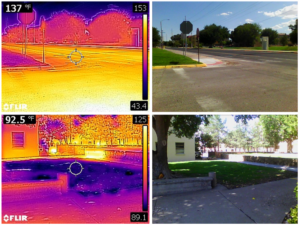

These images from the NIHHIS Urban Heat Island Mapping Campaign in Las Cruces, NM, show how the temperature can differ greatly (by 44.5 °F) between shaded grass and exposed pavement. Credit: David DuBois.

Source: heat.gov

The first phase of the research involves mapping heat islands* throughout the planning district. Researchers will measure the difference in summertime temperatures across the region in cities and neighborhoods versus the temps that would be expected in natural areas. It’s a means for assessing the magnitude of the impact of the built environment. And according to Nicole Keller, Resilience Planner at PlanRVA, heat islands can exist throughout the region.

“You think it’s just going to be in Richmond City or maybe Chesterfield, but you can have a heat island even in a rural county – any pocket where there is a lot of built infrastructure. It’s important for people to recognize that just because they live in a rural county doesn’t mean that they aren’t being affected by heat,” she says.

InVEST

The second part of the study uses a model called InVEST, which stands for Integrated Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Tradeoffs. The model puts a dollar value on a variety of ecosystem services. It maps all of the things on the ground – both natural and built – that mitigate extreme heat: tree canopy shade, evapotranspiration, albedo (the measure of light or radiation reflected by a surface) and proximity to green space, among them.“Once you compare these two measures, we can see where we’re already doing a good job fighting extreme heat and where we have opportunities for improvement,” Keller says. “With special regard to disenfranchised communities, we’ll find the low-hanging fruit, places where, if we invest a certain amount of money, we will have the most impact.”

The Social Layer

The third leg of the research tool is building a social vulnerability map that is specifically related to heat vulnerabilities*. When that map is layered on top of the other two maps, planners can get a clearer picture of the conditions across the region, and a subsequent analysis will enable them to see areas that are disproportionately impacted, assess priorities and make effective and prudent funding decisions related to mitigation.

“Let’s say the first two maps – the heat islands and cooling capacity – show us an area that is very hot and has no tree coverage, but the third map might tell us that that area is an industrial park. Because the use is non-residential, a locality might conclude that funds should be prioritized for investment in more highly populated areas,” Keller says.

PlanRVA is where the region comes to look ahead, and this research can help regional leaders make informed and forward-thinking decisions on how to best prepare Greater Richmond for the future. For more information about resilience planning initiatives led by PlanRVA, visit at https://planrva.org/environment/resilience/.

Next time: learn more about an innovative partnership between PlanRVA and Homeward in helping mitigate the impact of extreme heat on the region’s homeless population.